Filaments of Connection - from the Macrocosm to Microcosm, and back

- The heART of Ritual

- Mar 25, 2022

- 4 min read

When it comes to mythology and ancient indigenous wisdom it is generally accepted that the stars, constellations, and the cosmos itself can appear figuratively and metaphorically in the oldest spiritual concepts and stories. The sun, moon, and cycles of time may take the form of gods or goddesses, ancestor spirits or aspects of seasonal change.

Ancient astrology was used to divine prophecy and auspicious moments for important decisions, but entering new suns or years was also magically important for the healers, shaman and wisdom-keepers of all of our ancient ancestors.

Astronomical motifs, as well as meteors, comets, and eclipses are all sky phenomena which are interpreted as being depicted in ancient cave art by many archaeologists, as well as being understood as omens, signs and portents by the animistic practices surviving today which carry on the least interrupted traditions of native peoples around the world.

When indigenous healers describe entering the various Otherworlds and spirit domains for wisdom, we tend to reflexively imagine the inward journey accessing an outer world, a cosmos beyond our own where ancestors await the arduous spiritual seeker in order to impart wisdom.

It is often the case that ancient cave art has been interpreted as depicting a shaman travelling to the stars or celestial realms, past suns and nebulas, painted on cave walls as part of their journeying. But, there is another way of seeing these images which is just as cosmic but from a perspective which is just as important, but often overlooked.

I was struck by an image (micrograph) of a cell which I saw recently. It seemed familiar to me but I couldn't quite recall where I had seen it before. Then, I remembered it was a style of painting by indigenous people of The Southern Hemisphere which was associated with initiatory sacred knowledge and the ancestral realm.

Similar to this was the art and designs of the Sami and Ulchi of Western Asia and Eastern Europe, and before I knew it I was finding images and ancient art by indigenous North and South American peoples, before exploring the ancient cave art of the San tribes of Southern Africa.

Of course, here in Ireland we also have ancient native art, often described as abstract, although as Anthony Murphy has asked, is it really abstract, or are we just not seeing it as the ancients intended?

That got me thinking a bit more about how Irish carvings are also sometimes considered astronomical in nature, even though we have no proof that this was definitively the case, and, this is important, if there is *more* than one way in which to understand these images and designs.

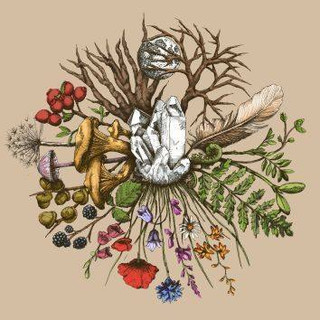

When we think about animism and the web of consciousness connection between all living things on our planet we often forget about the microscopic world of microbes, germs, bacteria, as well as the soil itself, the insects, the grasses and plants which determine what can grow and what can live and survive in a particular place. We are sometimes so comfortable today that our only concept of a spirit realm or otherworld is 'out there' instead of 'here', something bigger than ourselves instead of something part of ourselves. It's understandable, though.

For our ancestors, the land was not just part of who they were, but it was itself composed of their own generations of families and ancestors. The land was deity, in many ways. The origins of our oldest magical and spiritual beliefs tell us that all is one, but also that the maxim 'as above so below' applies both in a consciousness and physical sense. The words were not always the same, of course, but the meaning was.

In this context, the viewing of ancient symbols and art representing the microscopic aspects of life and landscape, and, time itself, were probably as apparent and as important to those who lived dependent upon the cycles of bird migration, the seasonal rise of rivers to fertilise soil, as were the slower shifts of the sky and stars.

The medicine healer travelled inwards to the ancestral realms for wisdom and healing, often implying, (outside the closed door of initiation), that to go inwards was to travel outwards. The holographic nature of Asian shamanism, of indigenous aboriginal wisdom, of the healer, was always to acknowledge the connection between the microscopic and macroscopic: as above, so below, in other words. So why would this not also be represented in art, stories and allegory? After all, the hero's journey is not just a path for a human being, but, in different and probably unfathomable ways, it is the song of life for all forms of consciousness on our planet.

Of course, what the shaman, medicine person, and indigenous teacher also tell us is that there is more to this journey. Not just a survival beyond the physical, but a return to something outside ourselves which we were always part of.

As we move towards Bealtaine, though, maybe I should rephrase that as ‘something we are always a part of, that is eternally *within* ourselves.’ (C.) David Halpin.